Peter Marshall is a well known name in squash history: a former world #2 (in 1995)

and protagonist of a brand-mark double-handed hitting technique. However, his

name is not only linked with his particular technique and great

achievements, but also with a disease that ruined in big part his

carrier and his ambitions of going one step further and becoming world

#1. Peter Marshall's Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) generated quiet some

question mark and debate in its time, but all the external controversy

was insignificant compared to the inner fight that Marshall himself

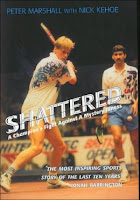

put into the understanding and handling of his disease. Writing (with the help of co-author Nick Kehoe)

a book about it became, I presume, part of the healing process. The book was published in

2000 under the title Shattered: A Champion's Fight Against a Mystery Illness; it's a very well written book analysing with honesty Marshall's personal and professional issues and

describing the surrounding world of squash in fine and entertaining

detail. In the below video you can see the last few rallies of a match between Peter Marshall and Jansher Khan, and underneath you may read on our in-depth review of the book (apologies if it seems almost as long as the book itself, but I got carried away as I found it really intriguing, maybe a fraction even more than James Willstrop's recent Shot and a Ghost).

The first part of Marshall's squash carrier was pretty straight forward. Even though he had a very unorthodox two-handed racket-technique inherited form his early childhood when he simply couldn't bear the weight of the heavy wooden rackets, he has won basically all the main British junior titles and became relatively quickly a world top10 player in the early nineties. At that time, Jansher Khan has already substituted Jahangir Khan at the top of the squash world (no one else in squash history has ever established such a dominance compared to the rest of the field as those two). Marshall was one of those players who got to the finals of the main tournaments just to be stopped all the time by Jansher.

However, whilst other players might have become disgusted and gutted with the constant defeats, Marshall put himself into a mindset where every defeat became a lesson to take in order to achieve the long-term goal: beating and substituting Jansher Khan as the world #1. It was not to be. By the time Marshall became world #2, his disease obliged him to stop playing professionally and hang up the racket for two years, just to make a short comeback tentative in 1997 (in which he still managed to beat the then up-and-coming sensation Jonathon Power), and then being out for another two years to make his ultimate comeback in 1999 when he managed to climb back very quickly into the world top10. Soon after though, he was out again, then for good.

So what was this disease, how come it came out at a peak-stage of Marshall 's carrier so close to the top of the world (rankings)? Was it purely a psychological problem as many have presumed or does CFS also have physiological roots? If yes, what was the link between the psychological and the physiological aspects?

At the very beginning, Marshall had to struggle even with the fact that the doctors couldn't really diagnose his disease. He's done all the tests, but there was nothing wrong with them. In a later stage, when at least someone came up with the name of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), he still had to face either scepticism or lack of knowledge about the eventual forms of treatment by the doctors.

Unlucky for Marshall, the disease started to become more specifically diagnosed/known by the medical world only after the end of his carrier. By then, it was commonly assumed that there is a viral infection at the origins of this disease. It is a virus (in Marshall's case glandular fever in his youth) that weakens the immune system which then will become more sensitive to other infections. Of course, not everybody who had glandular fever will have CFS and Marshall himself went up to world #2 before CFS struck him in such degree that he was not able to play anymore. Marshall comes to the conclusion that CFS was probably the result of a self-defensive mechanism of his body that he had put under exaggerated training regimes in order to try to fight the supremacy of Jansher Khan.

Marshall's idea was that Jansher covers the court too well, so there is no way to win rallies with quick winners; he presumed that the only way to win against him would be to make the rallies last as long as possible in order to tire his opponent and squeeze the points out of him. Marshall thought age too would be on his side, Jansher - even though extremely fit himself - must start to fade at some point. In the book Marshall refers to himself as probably one of the fittest athletes in the world of his time, and to get to this stage he was not shy to afflict his body with horrendous amount of stamina and muscle exercises. Only five years later, at his second comeback did he realise that what he did is commonly called over-training, which in his case - in the complexity of having had a weakened immune system and having had to climb a mountain called Jansher Khan - turned out to be fatal.

It must have been an interesting situation: there was the mind and iron will of Peter Marshall on one side to fight and beat the beast (Jansher) and there was on the other side the body of Peter Marshall that could just not cope with the mind's and will's projects. Marshall thought of himself exclusively in terms of mind and will; he considered his body as an everlasting tool that would execute anything he dictates him. I think mentally and psychologically that was the greatest error that Marshall committed: founding his fight against Jansher mostly on a physical basis (the idea of making their rallies last). By doing so, he basically admitted that he could not beat him with the racquet (shots) or with the head (deception/anticipation) and this in itself might have produced unconsciously a complex of inferiority. Not to talk about the fact - that Marshall himself describes so well - that Jansher's general tactics was exactly based on "rallying", and nobody was better than him in doing so, because he was more economical than anyone else in the history of squash in terms of movement but still as quick and agile as a panther.

And this is another great part of the book, where Marshall describes Jansher Khan's playing style in comparison with Jahangir Khan's.

Jahangir used to be an overwhelming warrior; from the very first moment he stepped on the court he was about to devour you. It was immediate and constant attacking; high pace, high position on the 'T', lot's of volleying. Add to this speed and fitness, and often he seamed to beat his opponents even before they put their feet on the court.

Jansher had a different approach. He was not a destroyer, he liked to play slow pace and didn't mind to let the rallies last long, allowing his opponents to settle and attack, to go for shots. He was using his opponents attacks to get them trapped; he was transforming their positive energies into negative, not with one shot, but with a sequence of shots and with a never before seen stubborn tenacity.

Personally I do think that from a psychological point of view Jansher must have been the tougher one to compete against. Jahangir was a terminator, what can you do? You are a professional so you try, but you are not surprised to lose quickly. With Jansher you might even fancy your chances, just to understand gradually that you have been trapped into a procedure called 'slow death'. The even more amazing thing about Jansher is that he has figured out and employed these almost philosophical tactics at a very young age; he beat Jahangir first at the age of 17 and became world #1 at 18. Jansher could afford these tactics for three reasons: 1) fitness 2) economy of movement 3) incredible anticipation.

Marshall was equal if not better in terms of fitness, but was way inferior in terms of economy of movement and anticipation. I know it's a constant debate in coaching whether one shall concentrate to improve his strength or work on his weaknesses. But I think when it comes to the highest standards, there is no way you will outplay your opponent by concentrating exclusively on your strong points and improving mostly only one aspect of the game. I think Peter Nicol demonstrated perfectly straight after Marshall's failure how to face and prepare against naturally more gifted players. Nowadays, Nick Matthew is a great example how to do it.

Today probably Matthew is the hardest trainer out there (just as Marshall used to be in his time) but he does not rely exclusively on his superior stamina and mental toughness; you can definitely see how with time he has constantly adjusted his game by learning from the naturally more talented players (Jonathon Power, Amr Shabana, Gregory Gaultier, Karim Darwish, James Willstrop, Ramy Ashour - to mention the most evident ones of his contemporaries).

But Matthew has already a whole institution behind him with an army of psychologists, physiotherapists and trainers. Marshall observes in his book bitterly that in his time coaching was not as scientific as it is nowadays and he did not have the same facilities that the current British players have at their disposition. He had to look for doctors himself and quiet a few of them were not very sympathetic with him; they had very little to advise and some of them were even sceptic about the reality factor of his illness. This, from a professional and ethic point of view is outrageous I think: whether the problem is psychologically or physically based, it is there, it creates real obstacles, therefore it has to be treated. It is in another question if you as a doctor are incapable of treating it; but then assume it and do not insult instead your patient.

In 1999 Marshall, after having tried all the official and alternative treatments proposed by that time, came to the conclusion that he had to change his mindset in order to be able to live a normal life and maybe even compete again on a professional level. He found that one of the antidepressants that he has been prescribed allowed him to feel a lot better when dosed carefully. In a first time the dose was too high and created panic and other disturbances, so he stopped taking it. Later, due to another doctor, he started to take it again, but only a quarter of the dose he used to take. It wasn't a perfect solution, but it helped a lot.

And this is exactly what Marshall had to understand and accept: there is probably no solution, but only ways to handle and keep under control the disease. The physical way to keep it under control was the antidepressant, the psychological way to handle the situation was to accept that there will be days when things go worse, and as soon as he feels tired he will have to stop training and rest as long as he does not feel better. He has to cope with this handicap, and if he does so, he will be more relaxed mentally, which on its turn will also help the body to relax and recover quicker. In 1995, when the disease started to turn up, he couldn't have adopted this mental approach; he was a young professional full of ambition and keen on giving it his all or even more if possible. As a professional sportsman he was taught to accept only the maximum end anything less would have worried him. By 1999, he became a lot less demanding and with four years of desperate searching for a normal life he has gained a different perspective of the importance of things. He realized that the main thing is to be capable playing squash and competing with the best. Everything beyond this will be considered a bonus.

Marshall might have committed an error by over-training at a certain point of his carrier. However, he has always accepted and assumed with nobility and a high level of intellectual honesty whatever destiny threw at him. And he still went up being world #2 which in itself is an amazing achievement that only a handful of players have achieved. He is also one of the five players ever to beat Jahangir Khan in an official match. En bref, there might be one or two things that Peter Marshall might regret, but there is much more he can be proud of. He is also a historical example of demonstrating in a coaching-wise somewhat orthodox country that technique is a totally personnel thing to be developed specifically by each player. Add to this that he has always been a really nice and humble person in the flesh. A pretty complete package to deserve squash fan's true appreciation and admiration.

If you want to read the book yourself, you shall be able to find used copies on amazon.com, amazon.co.uk or on ebay.co.uk.